Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Definition

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) denotes global left ventricular systolic dysfunction in the absence of hypertension, valve disease, or significant coronary artery disease.1 DCM is characterized by ventricular chamber enlargement and systolic dysfunction with normal left ventricular wall thickness.2 Right ventricular dilation and dysfunction may be present but are not necessary for the diagnosis. DCM is a largely irreversible form of primary heart muscle disease with no clear cause.

Gross heart specimen from a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy who died in end-stage heart failure. Defibrillator leads are in the right heart. The ventricles are dilated with normal ventricular wall thicknesses, imparting an appearance of thin ventricular walls. The ventricles are dilated more than the atria.

Epidemiology

The estimated prevalence of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is 1:2500. DCM is among the most common causes ofheart failure. Incidence of the disease discovered upon autopsy is estimated to be 4.5 cases per 100,000 population per year while clinical incidence is 2.45 cases per 100,000 population per year.3

Etiology

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) can be classified by cause as familial, primary without family history, or secondary (associated with or caused by other conditions). Approximately 2 of 3 patients have no known family history (sporadic DCM). About 15% of sporadic DCM arise from chronic myocarditis, leading to scarring and heart failure. Viruses that cause myocarditis include coxsackievirus, adenovirus, parvovirus, and HIV.

Noninflammatory etiologies and associations include alcoholism, anthracycline drugs, ingestion of metals, autoimmune and systemic disorders, and mitochondrial disorders. The distinction between primary and secondary DCM is sometimes blurred, as is the distinction between the cause and risk factor for many of these associated conditions. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy, which is considered to compose at least 25% of patients,2 is usually autosomal dominant, with X-linked autosomal recessive and mitochondrial inheritance occurring less frequently.

Noninflammatory etiologies and associations include alcoholism, anthracycline drugs, ingestion of metals, autoimmune and systemic disorders, and mitochondrial disorders. The distinction between primary and secondary DCM is sometimes blurred, as is the distinction between the cause and risk factor for many of these associated conditions. Familial dilated cardiomyopathy, which is considered to compose at least 25% of patients,2 is usually autosomal dominant, with X-linked autosomal recessive and mitochondrial inheritance occurring less frequently.

Location

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a diffuse process involving cardiomyocytes of both ventricles; atrial function is also decreased.

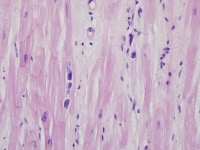

Heart section from a cardiac explant in a patient with end-stage cardiomyopathy. Note cardiomyocyte multinucleation. The change is nonspecific and can be seen in heart failure of any cause.

Clinical Features

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a progressive, usually irreversible disease causing heart failure, left ventricular contractile dysfunction, ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias, conduction system abnormalities, thromboembolism, and sudden death.2 DCM may manifest clinically at a wide range of ages, but most commonly occurs in the third or fourth decade of life. It is usually identified when limiting symptoms are severe, but arrhythmias or sudden death are uncommonly early manifestations. In family screening studies with echocardiography, asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic relatives may be identified. In contrast to arrhythmogenic and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias are typically prominent only after the onset of significant heart failure.

DCM is defined as increased left ventricular diastolic dimension and decreased shortening fraction, usually less than 25%. Note that postmortem ventricular measurements might underestimate the diameter measurement, as precise end-diastolic measurements are impossible.

The term “mildly dilated cardiomyopathy” describes patients with advanced heart failure without restrictive hemodynamics or significant left ventricular dilatation. A family history of DCM is present in over 50% of these patients. The clinical picture and prognosis of MDCM are very similar to those of typical DCM.4

Differential diagnosis

The clinical and pathologic differential diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy is to exclude secondary causes of heart failure. The distinction between coronary artery disease resulting in cardiomyopathy (ischemic cardiomyopathy) and primary DCM can be problematic. Some have suggested that the diagnosis of ischemic cardiomyopathy be made if coronary artery disease and concomitant global left ventricular dysfunction that is out of proportion to the coronary obstruction exists; for example, if an ejection fraction of less than 40% with less than or equal to 50% narrowing of a proximal or more than 50% narrowing of a distal artery is found. This definition of ischemic cardiomyopathy has been shown ineffective.5 The term ischemic cardiomyopathy is now generally reserved for patients with severe coronary disease and global LV dysfunction, typically with a healed transmural infarct.

Pathologically, the histologic features are nonspecific. Grossly, enlarged, dilated hearts can be seen in long-standing hypertensive heart disease, and valve disease and severe coronary disease should be excluded. At endomyocardial biopsy, amyloid, iron deposition, and significant inflammation should be excluded by routine staining supplemented by special stains. In addition, the clinical history that excludes other causes of heart failure should be elicited before a specific diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy is made.

DCM is defined as increased left ventricular diastolic dimension and decreased shortening fraction, usually less than 25%. Note that postmortem ventricular measurements might underestimate the diameter measurement, as precise end-diastolic measurements are impossible.

The term “mildly dilated cardiomyopathy” describes patients with advanced heart failure without restrictive hemodynamics or significant left ventricular dilatation. A family history of DCM is present in over 50% of these patients. The clinical picture and prognosis of MDCM are very similar to those of typical DCM.4

Differential diagnosis

The clinical and pathologic differential diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy is to exclude secondary causes of heart failure. The distinction between coronary artery disease resulting in cardiomyopathy (ischemic cardiomyopathy) and primary DCM can be problematic. Some have suggested that the diagnosis of ischemic cardiomyopathy be made if coronary artery disease and concomitant global left ventricular dysfunction that is out of proportion to the coronary obstruction exists; for example, if an ejection fraction of less than 40% with less than or equal to 50% narrowing of a proximal or more than 50% narrowing of a distal artery is found. This definition of ischemic cardiomyopathy has been shown ineffective.5 The term ischemic cardiomyopathy is now generally reserved for patients with severe coronary disease and global LV dysfunction, typically with a healed transmural infarct.

Pathologically, the histologic features are nonspecific. Grossly, enlarged, dilated hearts can be seen in long-standing hypertensive heart disease, and valve disease and severe coronary disease should be excluded. At endomyocardial biopsy, amyloid, iron deposition, and significant inflammation should be excluded by routine staining supplemented by special stains. In addition, the clinical history that excludes other causes of heart failure should be elicited before a specific diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy is made.

Gross Findings

The hallmark gross finding at autopsy is left ventricular dilatation, usually more than 4 cm. Cardiomegaly is usually considered a requisite for the diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy.6 The mean heart weight is about 600 g.7 Some patients with dilated cardiomyopathy have very little cardiac enlargement, and the diagnosis must be made on clinical grounds.4 Typically, 4-chamber dilatation that is greater in the ventricles than the atria is found. In patients with a history of atrial fibrillation, atrial dilatation may be prominent. At autopsy, measuring the chamber cavity at the level of the papillary muscles in a transverse cut best assesses left ventricular dilatation. Concomitant right ventricular dilatation results in the typical globular appearance of the heart.

Left ventricular wall thickness is often normal, in contrast to hypertensive cardiomyopathy with failure.8 Mitral insufficiency may result from papillary muscle dysfunction secondary to ventricular dilatation and changes in ventricular wall shape.6 In contrast, tricuspid regurgitation results from annular dilatation.7

Mural thrombi are common in patients who do not receive anticoagulation. Ventricular endocardial fibrous plaques, presumably a sequela of thrombi, occur in about 10% of cases.6 Mild diffuse or patchy endocardial fibrosis, especially toward the ventricular outflow tracts, is frequent and is likely a result of cardiac dilatation.

Left ventricular wall thickness is often normal, in contrast to hypertensive cardiomyopathy with failure.8 Mitral insufficiency may result from papillary muscle dysfunction secondary to ventricular dilatation and changes in ventricular wall shape.6 In contrast, tricuspid regurgitation results from annular dilatation.7

Mural thrombi are common in patients who do not receive anticoagulation. Ventricular endocardial fibrous plaques, presumably a sequela of thrombi, occur in about 10% of cases.6 Mild diffuse or patchy endocardial fibrosis, especially toward the ventricular outflow tracts, is frequent and is likely a result of cardiac dilatation.

Microscopic Findings

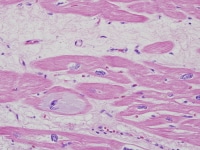

The histologic features of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) are nonspecific; therefore, it is a microscopic diagnosis of exclusion. In biopsies, the findings range from minimal variation in myocyte size to typical features of myofiber loss, interstitial fibrosis, and marked variation in myofiber size. The important features are negative findings, such as the lack of inflammation, amyloid, iron, and granulomas. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the diagnosis of DCM is primarily to exclude secondary causes. Endomyocardial biopsy may establish a specific diagnosis in approximately 25% of patients; these were primarily patients with amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, and adriamycin toxicity.

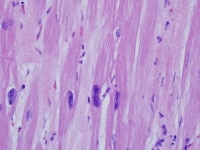

Heart section from a cardiac explant in a patient with end-stage cardiomyopathy. There is focal interstitial fibrosis. The change is nonspecific and can be seen in heart failure of any cause.

In explanted hearts, the findings are typically nonspecific diffuse findings of myocytes, including variation in size, nuclear variation, and interstitial fibrosis. Myofiber disarray and infiltrative processes such as amyloid are absent. Inflammatory cells, including mast cells that tend to be increased in areas of fibrosis, increase,9 but distinct infiltrates and myocyte necrosis are usually absent. Interstitial and replacement fibrosis are also common and correlate with inhomogeneous perfusion defects by SPECT.10

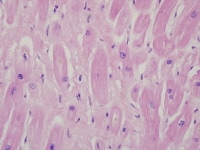

Heart section from a cardiac explant in a patient with end-stage cardiomyopathy. Note variation in nuclear size. The change is nonspecific and can be seen in heart failure of any cause.

Transmural scars may also occur in DCM. Quantitation of collagen has shown up to 4 times the normal collagen concentration, with a decrease in mature cross-linked collagen, correlating with an increase in neutrophil-type collagenase activity.11

Ultrastructurally,12 hypertrophied as well as atrophied myocytes exist, the volume density of myofibrils is reduced, and mitochondrial density is normal, but the mitochondria are more numerous and small.12

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical techniques are not useful for the diagnosis of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Immunolocalization of sarcomeric and cytoskeletal proteins have demonstrated abnormal distribution in explanted hearts from patients with DCM. Tubulin and desmin are increased in amount and irregularly distributed.12 Titin, a member of the sarcomeric skeleton family, is reduced, usually in areas where contractile material is lacking.12Connexin-43 is decreased.13 Increased myocyte cell death and apoptosis is found,14 along with regeneration of myocytes with the expression of PCNA and Ki-67.15

In patients with lamin-A mutations, ultrastructural immunolabeling showed absence of the nuclear envelope of patients with LMNA gene mutations.16 In cases of dystrophin-related DCM (up to 6% in males with DCM), immunohistochemical and molecular studies are essential to identify protein and gene defects.17

In patients with lamin-A mutations, ultrastructural immunolabeling showed absence of the nuclear envelope of patients with LMNA gene mutations.16 In cases of dystrophin-related DCM (up to 6% in males with DCM), immunohistochemical and molecular studies are essential to identify protein and gene defects.17

Molecular/Genetics

Autosomal dominant forms of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) are primarily caused by mutations in cytoskeletal proteins, and less commonly sarcomeric proteins, nuclear membrane, and transcriptional coactivator proteins, and intercalated disc protein genes. The most commonly identified are mutations of the LMNA gene, encoding the lamin A and C nuclear envelope proteins; these patients often have atrioventricular block (AVB). The X-linked gene responsible for Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, emerin (another nuclear lamin protein), may also cause DCM. Other X-linked diseases associated with DCM include muscular dystrophies (eg, Becker and Duchenne); these patients are more likely to have elevated serum CK.17 DCM may also occur in patients with mitochondrial myopathies and inherited metabolic disorders (eg, hemochromatosis).Sarcomeric proteins are increasingly being identified in familial DCM. These include alpha-cardiac actin; alpha-tropomyosin; cardiac troponin T, I, and C; beta- and alpha-myosin heavy chain; myosin binding protein C; muscle LIM protein; alpha-actinin-2; ZASP, and titin.2 In some families with sarcomeric mutations, hypertrophic and dilated phenotypes overlap, highlighting the plasticity of these genes and occasional genotypic-phenotypic discordance. These findings also underline the importance of defining cardiomyopathy by morphologic and not genetic features.

Prognosis and Predictive Factors

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is associated with less than 50% survival at 10 years. With better supportive care, 5-year and 10-year survival has been reported.18 Heart transplantation is the treatment of choice. Peripartum cardiomyopathy may be reversible in up to 50% of patients but often recurs with subsequent pregnancy. There is a negative association in DCM between survival and frequent ventricular tachyarrhythmias that required antiarrhythmic treatment or AICD placement.

Multimedia

| Media file 2: Heart section from a cardiac explant in a patient with end-stage cardiomyopathy. Note variation in nuclear size. The change is nonspecific and can be seen in heart failure of any cause. |

Keywords

dilated cardiomyopathy, cardiomyopathy, nonischemic cardiomyopathy, systolic dysfunction, heart failure, heart transplant

0 comments:

Post a Comment