EMERGENCY MEDICINE ARTICLES,

CBRNE - Anthrax Infection;

Introduction

Background

The term anthrakis means coal in Greek, and the disease is named after the black appearance of its cutaneous form.1 Anthrax is described in the Old Testament, by the poet Virgil, and by the Egyptians. At the end of the 19th century, Robert Koch's experiments with anthrax led to the original theory of bacteria and disease. John Bell's work in inhalational anthrax led to wool disinfection processes and the term woolsorter's disease.

Anthrax is caused by inhalation, skin exposure, or gastrointestinal (GI) absorption. Disease caused by inhalation is usually fatal, and symptoms usually begin days after exposure. This delay makes the initial exposure to Bacillus anthracis difficult to track.

An additional concern is use of anthrax as a biologic warfare agent. During the first Gulf War, Iraq reportedly produced 8500 L of anthrax. A total of 150,000 US troops were vaccinated with anthrax toxoid. Since October 2001, 22 confirmed or suspected cases of anthrax infection, disseminated via the US postal system, have been identified. Since there have been no cases of naturally occurring inhalational anthrax in the US since 1976, alarm should be raised for the occurrence of even a single infection.

Pathophysiology

Anthrax (B anthracis) is a large, spore-forming, gram-positive rod. Persistence of spores is aided by nitrogen and organic soil content, environmental pH greater than 6, and ambient temperature greater than 15°C. Drought or rainfall can trigger anthrax spore germination, while flies and vultures spread the spores.

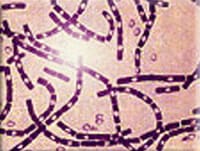

Anthrax infection. Polychrome methylene blue stain of Bacillus anthracis. Image courtesy of AVIP agency, Office of the Army Surgeon General, United States.

B anthracis has a diameter of 1-1.5 µm and a length of 3-10 µm. It grows in culture as gray-white colonies that measure 4-5 mm in diameter and have characteristic comma-shaped protrusions. Anthrax is differentiated from other gram-positive rods on culture by lack of hemolysis and motility and by preferential growth on phenylethyl alcohol blood agar with characteristic gelatin hydrolysis and salicin fermentation.

Virulence depends on the bacterial capsule and the toxin complex. The capsule is a poly-D-glutamic acid that protects against leukocytic phagocytosis and lysis. Experiments by Sterne demonstrated that the capsule is vital for pathogenicity.

Anthrax toxins are composed of 3 entities: a protective antigen, a lethal factor, and an edema factor. The protective antigen is an 83-kd protein that binds to cell receptors within a target tissue. Once bound, a fragment is cleaved free to expose an additional binding site. This site can combine with edema factor to form edema toxin or with lethal factor to form lethal toxin. Edema toxin acts by converting adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). Cellular cAMP levels are increased, leading to cellular edema within the target tissue. Lethal factor is not well understood, but recent work suggests that it may inhibit neutrophil phagocytosis, lyse macrophages, and cause release of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 1.

Frequency

United States

During the last 30 years, the indigenous US incidence of any anthrax infection has been less than 1 case per year. From 1955-1994, US cases totaled 235, with 224 cases of cutaneous anthrax, 11 cases of inhalational anthrax, and 20 fatalities. The last fatal case during this period occurred in 1976, when a home craftsman died of inhalational anthrax after working with yarn imported from Pakistan.

Before October 2001, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) investigated several threats in the United States, including Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, and California. Since October 2001, 22 confirmed or suspected cases of anthrax infection have been identified. Cases were reported from Florida, New York, New Jersey, the District of Columbia, and Connecticut. There were 11 confirmed cases of inhalational anthrax (5 deaths) and 7 confirmed and 4 suspected cases of cutaneous anthrax (no deaths). Seven cases were associated with occupational exposures in the postal service, and 2 cases had documented exposures to contaminated mail in the business office of a media company. No sources of exposure were identified for 2 women who were presumably exposed to secondarily contaminated mail. No reports in the literature have documented direct human-to-human transmission.

International

In 1958, approximately 100,000 cases of anthrax occurred worldwide. Exact figures do not exist because of reporting difficulties in Africa. Anthrax is endemic in Africa and Asia despite vaccination programs. Sporadic outbreaks have occurred as a result of both agricultural and military disruptions. During the 1978 Rhodesian civil war, failure of veterinary vaccination programs led to a human epidemic, causing 6500 anthrax cases and 100 fatalities. A mishap at a military microbiology facility in Sverdlovsk in the former Soviet Union in 1979 resulted in at least 66 deaths.1 Human anthrax often is associated with agricultural or industrial workers who come in contact with infected animal tissue.

Mortality/Morbidity

Anthrax is primarily zoonotic. Human anthrax cases are due to exposure through agriculture or industry. Those at highest risk are shepherds, farmers, and workers in facilities that use animal products, especially previously contaminated goat hair, wool, or bone. Most anthrax disease is cutaneous (95%). The remaining cases of the disease are inhalational (5%) and GI (<1%). Without treatment, the mortality rate of inhalational anthrax is approximately 95%.

Clinical

History

- Exposure may occur by contact with animals or animal products (eg, hides in African export shops).

- Military personnel and civilians may become exposed in biologic warfare situations.

- In October 2001, approximately 10,000 people across the eastern United States were advised to take antibiotics in the aftermath of anthrax exposure.

- No reports of direct human-to-human transmission exist in the literature.

Physical

Physical findings are nonspecific. The incubation period for all clinical manifestations is 1-6 days following exposure. The prodrome includes fever, malaise, and adenopathy. Inhalational anthrax, the most deadly form, can be mistaken for influenzalike illness, especially during the winter season. Unlike those with influenza or other viral respiratory illness, adults with inhalational anthrax are not contagious, they will have shortness of breath and vomiting, and they do not have sore throat or rhinorrhea.

- Cutaneous anthrax

- In the most common cutaneous form of anthrax, spores inoculate a host through skin lacerations, abrasions, or biting flies. Incubation is 2-5 days.

- The disease begins as a nondescript papule that becomes a 1-cm vesicle within 2 days. Occasionally, surrounding edema is severe and can lead to airway compromise if present in the neck.

- The skin in infected areas may become edematous and necrotic but not purulent. Such skin lesions have been described as "malignant pustules" after their characteristic appearance, despite being neither malignant nor pustular. Lesions are painless but on occasion are slightly pruritic.

- Spore germination occurs within macrophages at the site of inoculation. Anthrax bacilli are isolated easily from the vesicular lesions and can be observed on Gram stain. If prior treatment with antibiotics has occurred, the best way to determine infection is to perform serologic testing and punch biopsy at the edge of the lesion and examine by silver staining and immunohistochemical testing.

- The initial lesion ruptures after a week and progresses to a characteristic black eschar. The stages of skin infection occur despite treatment with antibiotics.

Anthrax infection. Cutaneous anthrax showing the typical black eschar. Photo courtesy of the Public Health Image Library, CDC, Atlanta, Ga.

- Differential diagnoses of the skin lesion include tularemia, plague, cutaneous diphtheria,Staphylococcus infections, Rickettsia infections, and orf (a viral disease of livestock).

- Cutaneous anthrax usually remains localized, but without treatment, it disseminates systemically in up to one fifth of cases. Antibiotic therapy prevents dissemination but does not affect the natural history of the lesion. With treatment, the mortality rate is approximately 1%.

- Inhalational anthrax

- Inhalational anthrax usually occurs in textile and tanning industries among workers handling contaminated animal wool, hair, and hides.

- Based on previous primate studies, the minimum infective dose ranges from 4000-8000 inhaled spores. Inhaled spores are ingested by pulmonary macrophages and then carried to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. Incubation is 1-6 days.

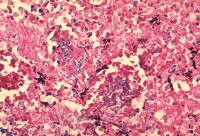

Anthrax infection. Histopathology of mediastinal lymph node showing a microcolony of Bacillus anthracis on Giemsa stain. Image courtesy of Dr Marshall Fox, Public Health Image Library, CDC, Atlanta, Ga.

- The spores undergo germination and multiplication and begin to elaborate toxins. After the lymph nodes become overwhelmed, bacteremia and death quickly ensue.

- Without treatment, the mortality rate of inhalational anthrax is approximately 95%.

- The clinical presentation is usually biphasic in nature.

- The initial stage begins with the onset of myalgia, malaise, fatigue, nonproductive cough, occasional sensation of retrosternal pressure, and fever. A transient improvement in symptomatology may occur after the first few days.

- The second stage, lasting 24 hours and often culminating in death, develops suddenly with the onset of acute respiratory distress, hypoxemia, and cyanosis. The patient may have mild fever; alternatively, the patient may have hypothermia and develop shock. Diaphoresis often is present; enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes may lead to partial tracheal compression and alarming stridor. Auscultation of the lungs is remarkable for crackles and signs of pleural effusions. Meningeal involvement may be present in up to 50% of cases; it usually is bloody and may be associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Decreased level of consciousness, meningismus, and coma may be present.

- A chest radiograph typically shows widening of the mediastinum and pleural effusions, whereas the parenchyma may appear normal. In a review of the 11 patients infected by anthrax in October 2001, chest radiographs from the initial examination showed mediastinal widening, paratracheal and hilar fullness, and pleural effusions or infiltrates. In some patients, the initial findings were subtle and not detected immediately.

- Gastrointestinal anthrax

- GI anthrax is a rare form of infection. It occurs from eating infected, undercooked meat. Only 11 cases have been reported, all in underdeveloped countries.

- Symptoms usually begin a few days after ingestion of the contaminated meat. Abdominal pain and fever occur first, followed by nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

- In this illness, spores invade GI mucosa. As spores are transported to mesenteric lymph nodes, replication and bacteremia begin. Ascites and ileus follow as the lymphatic system becomes occluded with the large number of bacilli. Peritoneal fluid is turbid with the presence of leukocytes and red blood cells from hemorrhagic adenitis. Vascular stasis occurs, and the stomach and intestine become edematous.

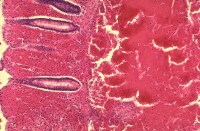

Anthrax infection. Histopathology of large intestine showing marked hemorrhage in the mucosa and submucosa. Image courtesy of Dr Marshall Fox, Public Health Image Library, CDC, Atlanta, Ga.

- In some cases, necrosis and ulceration at the site of infection produce GI hemorrhage. Severe abdominal pain, hematemesis, hematochezia, and, less often, watery diarrhea are presenting features. Shock occurs from interstitial and intraperitoneal volume losses.

- Anthrax toxin further causes intrinsic renal failure independent of prerenal azotemia.

- Death is rapid without antibiotic therapy and aggressive volume resuscitation. The mortality rate is 50%.

- Oropharyngeal anthrax

- Oropharyngeal anthrax is a more common form of GI anthrax and has occurred in epidemic settings.

- As a result of ingesting infected water buffalo meat, an outbreak of 24 cases occurred concurrently with 52 cases of cutaneous anthrax in Thailand in 1982. Of the 24 patients identified in the Thailand outbreak, all had been treated with antibiotics, and 3 died. The mortality rate in reported cases ranged from 12-50%.

- Typically, 2 days after ingestion of infected meat, fever and neck swelling occur in the presence of an oral cavity lesion. The lesion starts as an edematous area that becomes necrotic and forms a pseudomembrane within 2 weeks. Sore throat, dysphagia, respiratory distress, and oral bleeding also occur. Soft tissue edema and dramatic cervical lymph node enlargement follow.

- Recovery usually takes 3 weeks with antibiotic therapy.

- The reason the disease limits itself to the oropharyngeal area is unknown.

- Meningeal anthrax

- Meningeal anthrax is usually the result of bacteremia from the cutaneous, GI, or inhalational form of the disease. It also has occurred without a primary focus.

- The meninges are characteristically hemorrhagic and edematous.

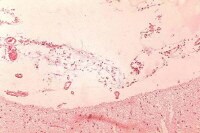

Anthrax infection. Histopathology of hemorrhagic meningitis in anthrax. Image courtesy of Dr Marshall Fox, Public Health Image Library, CDC, Atlanta, Ga.

- Of the Soviet cases that underwent autopsy, 21 (50%) of 42 had meningeal involvement.

- The mortality rate is near 100%.

Causes

Prior exposure to radiation, alcoholism, and underlying pulmonary disease are important risk factors for inhalational anthrax.

Based on several cases of anthrax with no known exposure in the October 2001 postal anthrax release, studies were performed to evaluate increased risks for inhalational anthrax. Risk is determined not only by bacterial virulence factors but also by the balance between infectious aerosol production and removal, pulmonary ventilation rate, duration of exposure, and host susceptibility factors. Dilution ventilation of the indoor environment is an important determinant of the risk for infection. Enhanced room ventilation, UV germicidal irradiation, and other engineering control measures may be used to decrease the risk for infection.

0 comments:

Post a Comment