Infectious Endocarditis

Definition

Endocarditis refers to endothelial damage with thrombosis on endocardial surfaces, typically on the heart valves. Two major types of endocarditis exist: infectious endocarditis, which has a microbial etiology, and noninfectious endocarditis.

Several terms have been used for these conditions, including (subacute) bacterial endocarditis for infectious endocarditis, and nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) or marantic endocarditis for noninfectious endocarditis. The term NBTE is still in current use, but the terms subacute bacterial endocarditis and NBTE are to be discouraged, as not all infectious are caused by bacteria.

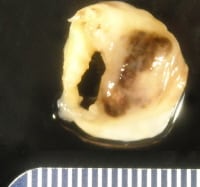

Mitral valve, endocarditis with valve destruction and vegetation. Note the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve, with an irregular vegetation on the atrial surface, resulting in valve destruction at the commissure between the anterior leaflet and the posterior leaflet.

Epidemiology

The population-based incidence of endocarditis is 4-10 per 100,000 per year, with a slightly higher rate in men.1,2The death rate due to endocarditis has been estimated at 1 per 100,000 per year, and over 10 times that amount in an urban population with a high rate of intravenous drug abuse.3 Endocarditis accounts for about 0.75 admissions per 1000 per year in large community hospitals.4

Etiology

Endocarditis begins as endothelial damage and sterile surface microthrombus, which, in the absence of bacteremia, regresses or grows into macrothrombi (noninfectious endocarditis).

Malformed stenotic valves, or especially regurgitant valves, are predisposed to endocarditis. In the presence of bacteremia or fungemia, even transient or those with low microbe counts, microthrombi become infected, by adhesion and colonization of the thrombotic surfaces. Growth of organisms results in an inflammatory response, with neutrophil infiltration, enlargement of the thrombus, recruitment of matrix metalloproteinases, and eventual destruction of collagen and cusp perforation. In approximately 25% of patients, however, neither structural valve abnormalities nor predisposing conditions are evident.

Congenital valve abnormalities, acquired valve disease, prostheses, and prior cardiac surgery for structural congenital heart disease increase the risk for endocarditis and are indications for antibiotic prophylaxis for dental and other invasive procedures. In nosocomial endocarditis, bacteremic conditions are present in nearly 40% of cases, and include intravenous drug abuse, hemodialysis, catheterizations, and intravascular devices.5

The organisms responsible for most cases of infectious endocarditis are gram-positive cocci: streptococci and, increasingly, staphylococci. The most common microbial infection is staphylococcus. Hospital-acquired infection is often associated with hemodialysis, prosthetic valvular infection, malignancies, and vascular interventions. Some cases of culture-negative endocarditis are caused by fastidious gram-negative organisms of the Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Actinobacillus, Actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella kingae (HACEK) group, which constitute approximately 1-3% of cases of community-acquired endocarditis on native and prosthetic valves, and may have a relatively good prognosis.

Organisms causing community-acquired endocarditis include the following:

Malformed stenotic valves, or especially regurgitant valves, are predisposed to endocarditis. In the presence of bacteremia or fungemia, even transient or those with low microbe counts, microthrombi become infected, by adhesion and colonization of the thrombotic surfaces. Growth of organisms results in an inflammatory response, with neutrophil infiltration, enlargement of the thrombus, recruitment of matrix metalloproteinases, and eventual destruction of collagen and cusp perforation. In approximately 25% of patients, however, neither structural valve abnormalities nor predisposing conditions are evident.

Congenital valve abnormalities, acquired valve disease, prostheses, and prior cardiac surgery for structural congenital heart disease increase the risk for endocarditis and are indications for antibiotic prophylaxis for dental and other invasive procedures. In nosocomial endocarditis, bacteremic conditions are present in nearly 40% of cases, and include intravenous drug abuse, hemodialysis, catheterizations, and intravascular devices.5

The organisms responsible for most cases of infectious endocarditis are gram-positive cocci: streptococci and, increasingly, staphylococci. The most common microbial infection is staphylococcus. Hospital-acquired infection is often associated with hemodialysis, prosthetic valvular infection, malignancies, and vascular interventions. Some cases of culture-negative endocarditis are caused by fastidious gram-negative organisms of the Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Actinobacillus, Actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella kingae (HACEK) group, which constitute approximately 1-3% of cases of community-acquired endocarditis on native and prosthetic valves, and may have a relatively good prognosis.

Organisms causing community-acquired endocarditis include the following:

- Staphylococcus aureus (30-50%; minority MRSA)

- Alpha-hemolytic (viridans) streptococci (10-35%)

- Enterococcus (5-10%)

- Culture negative (5-30%)

- Fungi (<5%)

- Staphylococcus epidermidis (coagulase negative; <5%)

- Others (eg, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Corynebacterium; <5%)

- S aureus (60-80%; majority MRSA)

- Alpha hemolytic streptococci (<5%)

- Enterococcus (5%)

- Culture negative (5%)

- Fungi (10%)

- S epidermidis (coagulase negative; <5%)

- Others (eg, E coli, Klebsiella, Corynebacterium; 5-10%)

The rate of culture-negative endocarditis varies from 7-33% and is increased in community-acquired infections because of antibiotic treatment prior to diagnosis.6 No association exists between culture negativity and underlying etiology or risk factors. If a full work-up is performed at a tertiary reference center, including serology and culture for esoteric organisms and polymerase chain reaction, an etiology is found in over 75% of cases of endocarditis with initial negative culture. The most common are C burnetii and Bartonella species.7

Location

Endocarditis generally refers to inflammation on the valve leaflets, although the endocardial lining of the atrium and ventricles may also be involved, especially after surgery. The process tends to begin on the lines of closure, where the pressure is greatest (atrial surfaces of the atrioventricular valves and the ventricular surfaces of the semilunar valves).

The valves most commonly infected are left-sided valves, with approximately equal frequency between mitral and aortic valves. Vegetations on the mitral valve can extend onto the noncoronary and left cusps of the aortic valve, as they are contiguous, and double aortic and mitral valve replacements are not rare. Left-sided valves are more frequent, even in drug addicts, than right-sided endocarditis,3 although infections of the tricuspid and pulmonary valves are highly suspicious of intravenous drug abuse. Tricuspid valve endocarditis may occur in community-acquired infection, usually in intravenous drug addicts, or hospital-acquired infections from implanted devices. Isolated pulmonary valve endocarditis is rare and may cause confusing clinical symptoms.

The valves most commonly infected are left-sided valves, with approximately equal frequency between mitral and aortic valves. Vegetations on the mitral valve can extend onto the noncoronary and left cusps of the aortic valve, as they are contiguous, and double aortic and mitral valve replacements are not rare. Left-sided valves are more frequent, even in drug addicts, than right-sided endocarditis,3 although infections of the tricuspid and pulmonary valves are highly suspicious of intravenous drug abuse. Tricuspid valve endocarditis may occur in community-acquired infection, usually in intravenous drug addicts, or hospital-acquired infections from implanted devices. Isolated pulmonary valve endocarditis is rare and may cause confusing clinical symptoms.

Clinical Features

The clinical symptoms arise from valvular insufficiency, with concomitant infectious symptoms. The classic signs of Osler nodes and Janeway lesions are increasingly uncommon, but microembolic phenomena such as splinter hemorrhages, Roth spots, and glomerulonephritis are still frequently observed in patients in the 21st century. Previously, infectious endocarditis has been diagnosed using clinical criteria (Duke criteria), dividing cases into possible and probable endocarditis, although current imaging modalities, especially transesophageal echocardiography and computed tomography, have largely supplanted other tests.

Treatment of infectious endocarditis includes antibiotics, and surgery if the valve is irreversibly insufficient. Surgical options include replacement, and repair if possible. In general, between 14% and 37% of cases require surgery.

Gross Findings

The valve may appear hemorrhagic and roughened, in early or treated lesions, with vegetations that may be inconspicuous or large. Especially bulky vegetations are typical of fungal endocarditis. Perforation of the valve leaflet is nearly pathognomonic for later stage endocarditis, because only infectious processes result in significant valve tissue destruction. In autopsy specimens, discrete areas of endocardial fibrosis, or jet lesions, may be seen on the atrial surfaces in cases of atrioventricular valve endocarditis, or the ventricular outflow in aortic or pulmonary endocarditis.

Upon autopsy, or with complete valve replacement, many valves demonstrate underling pathology such as bicuspid aortic valve, mitral valve prolapse, or postinflammatory valve disease, predisposing the patient to endocarditis.

Upon autopsy, or with complete valve replacement, many valves demonstrate underling pathology such as bicuspid aortic valve, mitral valve prolapse, or postinflammatory valve disease, predisposing the patient to endocarditis.

2. Aortic valve, healed endocarditis. Note the gaping hole with the fibrous rim, and a small strand at the free edge. The hole is at the line of closure. The affected valve is the left cusp. Note right non-coronary cusp (immediate to the left in this image) demonstrates a small, multi-channeled fenestration, at the commissure, immediate adjacent to similar fenestrations in the left coronary cusp. These are physiologic lesions occurring with age and are unrelated to endocarditis.

Aortic valve, bicuspid, with infectious endocarditis. In this excised valve, note the bulky vegetations on the ventricular surfaces, with distortion of the valve surfaces.

Mitral valve, postrheumatic, with infectious endocarditis. A defect is seen in the scarred valve, with focal surface hemorrhage. The patient also underwent aortic valve replacement, as there was contiguous infection.

Microscopic Findings

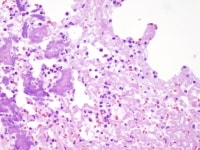

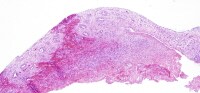

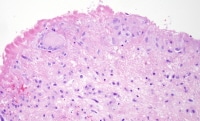

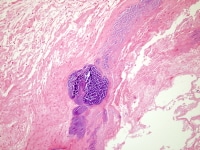

Two features are always present in infectious endocarditis: inflammation and surface thrombus. Depending on the duration of infection and treatment, the inflammation may be primarily neutrophilic or mostly chronic. Macrophage giant cells are common, especially toward the luminal surface. Organizing and organized thrombi with fibrosis are common in lesions that have been present for weeks or more. In acute lesions, clusters of organisms are frequently found, often gram-positive cocci, with the acute exudate and surface thrombus.

The surface of the valves, in most cases, demonstrates areas of acute neutrophilic inflammation with admixed fibrin and platelets. Degenerated bacterial colonies are seen at the left. Also, areas of microcalcification may mimic bacterial deposits.

Infectious endocarditis, subacute phase. Hemorrhage and prominent granulation tissue with neovascularity is apparent throughout. This aortic valve showed fibrin exudate on the ventricular surface (below), with more prominent organization and granulation on the aortic surface (above).

Infectious endocarditis, surface of valve leaflet with fibrin; higher magnification of Media file 6. A chronic infiltrate is seen, just under the denuded thrombosed surface, with primarily macrophages and focal macrophage giant cells.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry has been used for the detection of fastidious bacteria in cases of culture-negative endocarditis, specifically for Coxiella and Legionella infection. Immunohistochemical studies of these organisms are generally restricted to reference laboratories with special expertise in identifying infectious agents.

Bioprosthetic valve with endocarditis. Note the large bacterial colony (staphylococci by culture) in the absence of significant inflammation; the xenograft tissue is not viable, and nuclear detail is not apparent.

Molecular/Genetics

Polymerase chain reactions have been used for the detection of DNA specific for fastidious bacteria in culture-negative bacteria. Specific organisms that have been tested in this way include rickettsia (Coxiella, Bartonella, andTropheryma whipplei (Whipple disease)

Prognosis and Predictive Factors

The overall mortality of infectious endocarditis is approximately 20-25% and is increased with advanced patient age, left-sided disease, methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) infection, and chronic renal failure. For staphylococcal endocarditis, mortality is associated with age 60 years or older, female gender, community-acquired infection, absence of heart murmur, presence of congestive heart failure, and central nervous system involvement.8 The mortality rate of MRSA endocarditis in hemodialysis patients is as high as 90%.9 The long-term prognosis of patients with negative blood culture infective endocarditis has been found to be similar to that of patients with positive blood culture infective endocarditis across all age ranges.

Multimedia

| Media file 3: Aortic valve, bicuspid, with infectious endocarditis. In this excised valve, note the bulky vegetations on the ventricular surfaces, with distortion of the valve surfaces. |

Keywords

infectious endocarditis, subacute bacterial endocarditis for infectious endocarditis, nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis, NBTE, marantic endocarditis for noninfectious endocarditis, subacute bacterial endocarditis

0 comments:

Post a Comment